|

|

|

|

"My thoughts require no reading.

Let the rock that protects them be but a stage for singing

crickets."

--note found at the

Labyrinth

Created

by Helena Mazzariello, a Montclair artist, psychic, and shamanic

practitioner, as "a gift to the world" the Mazzariello Labyrinth,

commonly known as "Mazzariello's Maze," was originally laid out in the

form of a classical labyrinth.

Located in Sibley Volcanic Regional Preserve, in the East Bay

Regional Park District, in the hills above Oakland, California, the

Mazzariello Labyrinth (also dubbed the "Volcanic Witch Project") is in

a remote location, ideally suited as a place of serenity and

contemplation. Those who take the time to trek the extra distance to

reach the site, enter and walk the Labyrinth, pray, meditate, or simply

examine the messages and talismans left in the center are rewarded with

an experience that is profoundly spiritual. A total absence of clergy

and congregation, the sensation is quiet and humble, yet up front and

personal.

For some, the Labyrinth is the catalyst for a true spiritual

awakening. It embodies man's unending religious quest and represents

the frontier of the very limits of our present knowledge of the

mystical world.

Loosely defined under a much broader term: "a circle of stones"

labyrinths have been built since ancient times by almost every religion

in the world for healing and guidance. Being "a circle of stones" a set

of stones ceremonially placed on the ground to magnify spiritual

energy, the Mazzariello Labyrinth takes its rightful place along with

sites such as Stonehenge, in England, and the ancient Medicine Wheels

built by the native American Indians of North and South America.

But

the Mazzariello Labyrinth is unique. Try a web search of the word

“labyrinth” and discover for yourself that no other labyrinth across

the North American continent has anywhere near the untamed, aesthetic

beauty and rugged surroundings of the Mazzariello Labyrinth. Literally

born of volcanic fire and brimstone, the Mazzariello Labyrinth is

positioned at a geologic and spiritual crossroads, where the orient

meets the American west.

The

Mazzariello Labyrinth serves a diverse group of visitors for a range of

purposes. Although no more than several people can be usually found at

the Labyrinth at any given time, the site receives visitors 24 hours a

day, 7 days a week. The Labyrinth plays a small yet essential part in

the lives of many.

And the Friends of

the Labyrinth desire to keep it that way.

The

purpose for the Friends of the Labyrinth is to help maintain and

preserve a clean, welcome, and quality spiritual experience at the

Labyrinth. While important, this is actually accomplished with a

minimum of effort. But it is a fact of life that good things just

sometimes don’t last, and future situations may require that more

specific efforts and skills come into play from those who truly value

the Labyrinth.

It’s

no secret that the continued existence of the Labyrinth is not a given.

One would do well to recall the fate of another unofficial sacred site,

located behind the Japanese Tea Garden, in Golden

Gate Park, San

Francisco. Similar in many ways to the

Labyrinth, it was a striking assembly of loosely organized rubble with

a central cairn, replete with interfaith offerings and incense.

Slightly

smaller than the Labyrinth, no defined path inside, but the magic was

there. Known and visited by an eclectic assortment of worshippers who

made pilgrimages there from around the world, the site was quietly

dismantled and unceremoniously disposed of by park staffs.

Legality: The

mere presence of the Mazzariello Labyrinth violates laws and codes of

the East Bay Regional Park District. Although warmly embraced by some

park officials, their sanctions of the Labyrinth are unofficial. As a

fairly recent feature to the area, the Labyrinth has not yet passed the

test of time.

Perceived Fire Hazard:

Some homeowners in the region feel that the Labyrinth is a

potential fire hazard, pointing out the candles and incense often found

in the cairn at its center. The Friends of the Labyrinth also feel that

the fire danger conditions at the Labyrinth should be regarded as

extremely high, especially during the dry season that extends from May

to November. But the burning of candles and incense seems to be an

unenforceable feature at any remote site.

Recently,

someone has come up with and implemented a simple, if not elegant,

solution by crafting and placing a rustic, solar powered light that

warms the central cairn with a dim glow in the darkness. Also, the

interior of the central cairn has been rearranged to include a

separate, deep and narrow pit to isolate and contain items that glow or

smolder. Loose candles, matches, lighters and scrap papers found at the

Labyrinth are regularly disposed of by the Friends of the Labyrinth (as

well as park employees) to discourage the casual visitor from

lighting things and simply walking away. As a result, the open burning

of candles and incense at the Labyrinth has dropped off to nil.

Environmental:

Although the Labyrinth is in an abandoned quarry, a totally man made

canyon, nature has re-asserted itself and a seasonal pond has

formed at the Labyrinth's north end. This feature is a unique

biological and ecological site and as such could come under the

jurisdiction of a conservation group or some other environmental

entity. Such a move, while laudable, could ultimately bar public entry

into the tiny watershed of the Labyrinth.

Land

Fill:

The East Bay Municipal Utility District and the East Bay Regional Park

District have recently completed a landfill in a quarried area of the

north end of Sibley Volcanic Regional Park, bordering the Stone

Property. The project was given the expressed mission of

"... recontouring and seeding the project area to create a more

park-like setting" and deposited 100,000 cubic yards of clean fill in

the area.

Likewise,

the Labyrinth could be threatened by a similar project. In 2003, a

hiker fell down a cliff face at the Labyrinth, requireing an

emergency medical litter. Admittedly, parts of the canyon of

the Labyrinth can be steep and dangerous. And this is the age

of the lawsuit. One local municipality is seriously contemplating

the absurd: the removal of all trees from the city's sidewalks,

just to stem the trend of frivilous lawsuits that are causing

massive hemmoraging of the city's coffers.

The

Friends of the Labyrinth affectionately call the abandoned quarry

of the Labyrinth a "canyon." An opportunistic plaintiff

could declare the abandoned quarry of the Labyrinth "an open

mine."

Summary:

In the event any of the above scenarios escalate to a clear and present

level, the Friends of the Labyrinth intend to serve as a grass roots

forum, to collectively remind park officials, and alert the public that

these are public lands, open to all. The East Bay Regional Park

District has been specifically entrusted with the preservation and

maintenance of all natural, as well as cultural, resources within

its boundaries, and managing these public treasures wisely.

Our

existence is known to visitors of the Labyrinth and others via the

internet. The Friends of the Labyrinth, being in communication with

each other, are naturally positioned to actively lobby for the

Labyrinth if it, or public access to the Labyrinth, seems threatened.

Outreach

and Fellowship:

While the main features of the Labyrinth are contemplation and

solitude, it is a fact that small groups of people sometimes do visit

the site. The Friends of the Labyrinth feel that there is a genuine

interest among some visitors to participate in, or simply observe with

fascination, ritual ceremonies and mystical events at the Labyrinth.

Those who already practice rituals at the Labyrinth, now in a very

private way, are considering posting open invitations at this webspace,

to provide an occasional introduction of just some of the wonderful

things that are possible at the Labyrinth.

The

Friends of the Labyrinth have no intentions of “booking up” the

Labyrinth, only to get others to feel a part of it and adopt it as

their own.

YOU

are a Friend of the Labyrinth: It

makes no difference whether you visit the Labyrinth frequently, or only

occasionally, it’s yours if you simply feel that you have a stake in

it. Careful to not succumb to the burdens and trappings of congregation,

the Friends of the Labyrinth have no meetings and rely solely in the

internet for communication, with warm, chance encounters at the

Labyrinth. Consider this webspace as a voice for your thoughts and

feelings about the Labyrinth.

Everything

you always wanted to know about the Labyrinth *

*

But were afraid to ask:

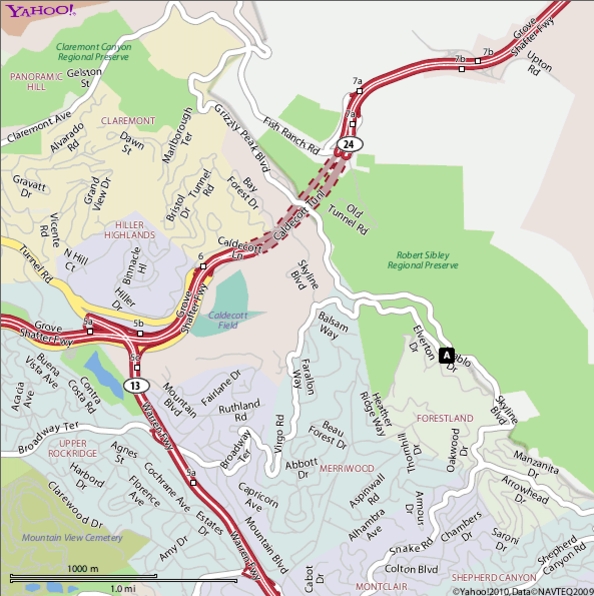

The

Labyrinth is located precisely at:

Longitude: 122 degrees west,

11 minutes, 25 seconds (-122.19043)

Latitude:

37 degrees north, 51 minutes, 11 seconds ( 37.85304)

Okay...

65 feet (20 meters) below Post #4, in the quarry pit, described in the

interpretive trail guide, in Sibley Volcanic Regional Preserve, in the

East Bay Regional Park District, located in the hills above Oakland,

California.

Not quite a ¾ mile, gentle hill-and-dell walk from an easily accessible

trailhead, one will encounter no more than about a 200 foot (61 meters)

change in vertical in getting there. The Labyrinth is about 1,575 feet

(480 meters) above sea level.

From

Post #4, take the short, narrow dirt road that leads south (to your

right, when facing the Labyrinth from above), then loops back north and

down into the quarry pit, ending at the Labyrinth. Avoid scrambling

down any trails directly to the Labyrinth as the slopes at the quarry

(actually a gravel quarry) are steep, unstable and quite dangerous.

It’s not uncommon for visitors to experience at least one minor

landslide at some time during their short visit. It’s just a reminder

of nature reclaiming itself, taking on a more natural, stable

configuration to the landscape.

The

Labyrinth was built, during the spring equinox in 1990, by Helena

Mazzariello (b. c.1960-

), in an area that she routinely took her goats to

graze. She originally layed out the Labyrinth as a

classical (or 7-circuit), left-handed, earthen labyrinth.

But her labyrinth quickly took on a life of its own as

hikers, now attracted to the site, began to build it up as a rock

labyrinth before Helena could finish it.

Labyrinths are

described by how many concentric circuits or paths they contain, and

the first turn in this labyrinth is to the left. Unlike a maze

(and even some labyrinths), a classical

labyrinth has a single, well-defined path that leads to the center with

no dead ends, no loops and no forks. All classical labyrinths share the

basic features of an entrance, a single circuitous path and a center

(aka cairn, altar, eye, fire pit, or shrine).

Some

of the earliest forms of the labyrinth are found in Crete,

dating back to 1500 BC. The legend of Theseus and the Minotaur

generally comes to mind at the mention of the word ‘labyrinth,’ but few

today know and recognize the labyrinth symbol. So important was the

labyrinth in ancient Crete that it was minted

on coins and inscribed on pottery of the time.

An

amazing aspect of the classical labyrinth is that historical variations

of its 7-circuit structure can be found throughout Europe, as well as

the orient, and even pre-columbian North and South America.

An

additional rogue path was later added to the Mazzariello Labyrinth by

someone, obviously on a lark, that extended the original entrance from

the south, around to the now familiar northwest entrance. The Friends

of the Labyrinth feel this addition adds a funky, yet special California

twist to the experience. The Mazzariello Labyrinth was the

first of five labyrinths built throughout the Sibley Volcanic

Regional Preserve and is, by far, the largest and most visited.

Urban

legends persist, of other labyrinths having been built in the

area of present day Sibley Volcanic Regional Preserve, prior to

1990 -and even during the 1930's and

1940's. Unfortunately, thorough studies of high resolution

black and white aerial photo archives of the era only prove a void of

such activities.

| North |

|

| Aerial View

of the Labyrinth |

In

traditional fashion, the Labyrinth was carefully laid out to a

north-south and east-west orientation. Measuring 55 feet (16.76 meters)

across, north to south, and spanning 57 feet 5 inches (17.5 meters),

east to west. Walking the Labyrinth, from the opening to the center and

back out again, one will cover a total distance of 1,352 feet (412

meters). That's the equivalent length of 4 ½ football fields, carefully

laid out in a very small place.

| North |

|

| Aerial View

of Labyrinth Canyon |

Due

to its location, at the bottom of a small but steep canyon, the length

of a typical day at the Labyrinth (or the time the sun's direct rays

warm its center) is shortened by about 4 hours, 42 minutes. While not

important to the casual visitor, the actual moment of sunrise and

sunset is crucial in some rituals. It's also a concern to those who

desire to plan a visit that avoids the unpleasant extremes in

temperature that are so common with the summer and winter seasons.

In the summer, actual sunrise

at the Labyrinth, the moment when the sun's rays strike the central

cairn, will be about 2 hours, 9 minutes (more or less) later than the

daily sunrise posted in local weather forecasts.

In the fall and spring,

actual sunrise at the Labyrinth will be about 1 hour, 54

minutes (more or less) later than the daily sunrise posted in local

weather forecasts.

In the winter, actual sunrise

at the Labyrinth will be about 1 hour, 19 minutes (more or less) later

than the daily sunrise posted in local weather forecasts.

The

sun's rays will sweep in from the west, across the floor of the

canyon, toward the central cairn at an average rate (ever slowing)

of 1.24 feet (.38 meters) per minute.

In the summer, actual sunset

at the Labyrinth, the moment when the sun's rays cease to strike the

central cairn, will be about 2 hours, 40 minutes (more or less) before

the daily sunset posted in local weather forecasts.

In the fall and spring, actual sunset

at the Labyrinth, the moment when the sun's rays cease to strike the

central cairn, will be about 3 hours, 9 minutes (more or less) before

the daily sunset posted in local weather forecasts.

In the winter, actual sunset

at the Labyrinth, the moment when the sun's rays cease to strike the

central cairn, will be about 3 hours, 24 minutes (more or less) before

the daily sunset posted in local weather forecasts.

The

shadow of the canyon wall will sweep in from the west, across the floor

of the canyon, toward the central cairn at an average rate (ever

accelerating) of almost 1 foot (.29 meters) per minute.

While

protected from the high winds that frequent the nearby ridges, the

Labyrinth does have a prevailing draft, from the east. The prevailing

wind in the surrounding area is a constant Pacific breeze from the

west. But when it passes over the canyon of the Labyrinth, a highly

localized, low-pressure system is created. The net effect is that the

Pacific winds, from

the west, are pulled down over the Labyrinth, going into a horizontal

roll that gently blows back, to the west, across the

ground level of the Labyrinth.

Heavy fog, rolling in from the Pacific

Ocean,

is a common evening and early morning feature at the Labyrinth, giving

it an eerie, mystical feeling. The fog bank rarely advances much

farther eastward than the Labyrinth and the east bay hills and usually

dissipates by midmorning.

The

Labyrinth experiences about one earthquake a year, 2.8 average

magnitude, originating within a 3.1 mile (5 kilometer) radius

of the Labyrinth, from an average depth of 5 miles (8

kilometers) below the canyon floor.

| Sibley

Volcanic Regional Preserve |

|

| (click

image to view at full size) |

| Sibley

Volcanic Regional Preserve |

|

| (click

anywhere in image to go directly to Sibley Volcanic Regional Preserve's

informative website) |

It’s

not uncommon for Sibley Regional Preserve (as well as other regional

parks) to be temporarily closed due to dry weather conditions that

could cause an extreme fire hazard, putting hikers at risk (it’s

impossible to outrun a western wildfire).

Before

your visit, it’s a good idea to phone the East Bay Regional Park Office

and Trail Closure Hotline for a recorded message as to specific park

closures.

Their

toll-free number is: 1-888-327-2757 Select option 4 on the

voice message menu, and then select option 2 on the submenu, for the

latest info on any trail closures.

Also: East Bay

Regional Park Trail Closure Hotlink: http://www.ebparks.org/closure

|

|

Mountain Lions at

the Labyrinth:

(aka puma,

Felis concolor)

The

Labyrinth is located in mountain lion country, which means that when

you disembark from your car at the trailhead, you become a part of the

food chain. Actually, while mountain lion sightings are not uncommon in

the hills of the East Bay, there has been no record of a

mountain lion ever having attacked a person in the area of the

Labyrinth. But, in 2004, a mountain lion was killed

in the county, for public safety reasons. Mountain lion attacks on

humans are on the increase and the Park District encourages caution

when hiking or biking in open spaces in the East Bay.

Rattlesnakes,

scorpions, and tarantulas are also native to the area of the Labyrinth.

And, like the mountain lion, are just a few of the many realities that

give the Labyrinth a special, tough edge.

Mountain

lions are generally elusive and wary of people, but, like any wildlife,

they can be potentially dangerous. Here are some guidelines in dealing

with the mountain lion threat:

- Do not hike alone. A

mountain lion will usually only stalk solitary people. Go in groups,

with adults supervising children.

Keep children close to you. Mountain lions seem

especially drawn to children. Keep children within your sight at all

times.

Do not approach a

mountain lion. Most mountain lions will try to avoid a

confrontation. Give them a way to escape.

Do

not run from a mountain lion.

A mountain lion can out-sprint a race horse. Running may also

stimulate a mountain lion's instinct to chase. Instead, stand and face

the animal. Make eye contact. If there are small children there, pick

them up if possible so they don't panic and run. Although it may be

awkward, pick them up without bending over or turning away from the

mountain lion.

Do

not crouch or bend over. A

human standing up is just not the right shape for a cat's prey. On the

other hand, a person squatting or bending over looks a lot like a

four-legged prey animal. When in mountain lion country, avoid

squatting, crouching or bending over, even when picking up children.

Appear

larger. Raise

your arms. Open your jacket if you are wearing one. Again, pick up

small children. Throw stones, branches, or whatever you can reach

without crouching or turning your back. Wave your arms slowly and speak

firmly in a loud voice. The idea is to convince the mountain lion that

you are not prey and that you may be a danger to it.

Fight

back if attacked.

Although a 160 pound mountain lion is fully capable of downing an

800 pound elk, many potential victims have fought back

successfully with rocks, sticks, caps, jackets, garden tools and their

bare hands. Since a mountain lion usually tries to bite the head or

neck, try to remain standing and face the attacking animal.

If

you see a mountain lion in a Regional Park, remember the date, time,

location, and exact circumstances. Report it to the Sibley Volcanic

Regional Preserve park office: 1-888-327-2757), select option 3

from the voice menu, and then select extension 4554 to talk

directly to a park staff.

In the case of threatening

behavior, immediately call 9-1-1, or 510-881-1121, from a cell phone,

24 hours a day.

Rattlesnakes

at the Labyrinth:

The Northern Pacific

Rattlesnake

(Crotelus viridis)

Rattlesnakes

are out and about in the area of the Labyrinth, becoming more active as

the weather gets warmer. If you hear a rattlesnake shaking its rattle,

back away. The snake is issuing a warning, and if the warning is

ignored, it may bite. There are many factors (temperature being the

most important) that determine how a snake will react when confronted

by a human. Rattlesnakes should always be observed from a safe distance

and are never safe to handle. Even dead ones can retain some

neurological reflexes, and "road kills" have been known to bite.

Dogs,

too, are occasionally bitten by rattlesnakes, because dogs

are curious by nature and explore with their noses. They tend to run

right up to rattlesnakes, barking and sniffing. So keep your dog under

control at all times.

The

loud buzzing rattler sound coupled with a high rising and very

threatening coil is usually ample identification information for those

in the field. Rattlesnakes have a triangular head that's noticeably

larger than their neck, a thick, non-glossy body, and a blunt tail with

the rattles on the end. When alarmed or threatened, they hiss and

rattle, creating a sound like sizzling bacon. And rattlesnakes simply

look mean-spirited.

Gopher

snakes, a non-venomous (harmless) species also common to the area

of the Labyrinth are, at first glance, quite often confused with

rattlesnakes. But gopher snakes have a head only slightly larger

than their neck. And their bodies are slender and glossy, their tails

are pointed, and they have no rattles. However, when threatened, they

sometimes hiss and thrash their tails around in dry grass and leaves,

creating a rattlesnake-like sound.

Rather

than relying on your skill at differentiating, it's best not to disturb

any snake or for that matter any other wildlife in the regional parks.

Just observe from a distance and enjoy the experience. If you find a

rattlesnake by a picnic table or other developed area, don't attempt to

deal with it yourself. Notify park staff immediately. Park staff

generally do not kill rattlesnakes but relocate them to areas less

visited by humans.

Rattlesnakes

found in the area of the Labyrinth are the Northern Pacific

Rattlesnake, a subspecies of the Western Rattlesnake. These are not

aggressive creatures. They do not initiate attacks, and they certainly

won't chase people down the trails. But they are largely defensive and

tend to stand their ground if provoked.

Rattlesnakes

should be considered armed and dangerous with well-developed

fangs and poison delivery system. A rattlesnake is classified as having

hemotoxic venom that attacks the blood system of its prey. The venom is

a complex mixture of proteins that acts primarily on a victim's blood

tissue. While not as potent as, say, a cobra, the rattlesnake

is far better equipped than a cobra to deliver its venom,

elevating the rattlesnake's status as one of the world's most

dangerous snakes.

Rattlesnakes belong

to a group of snakes known as pit vipers. These dangerous snakes have a

heat-sensitive sensory organ on each side of the head that enables them

to locate warm-blooded prey and strike accurately, even in the dark.

The curved, hollow fangs are normally folded back along the jaw. When a

rattlesnake strikes, the fangs rapidly swing forward and fill with

venom as the mouth opens.

Rattlesnake

young, which have a blunt horny button at the tip of the tail, are

born alive and are equally deadly. They have only one poison fang, but,

unlike the adult rattlesnake, release all of their venom in one strike.

The problem is that rattlesnake young, unlike adult rattlesnakes,

are quite cute and are more likely to be picked up and handled.

Symptoms

of a rattlesnake bite include swelling, pain, weakness, giddiness,

breathing difficulty, hemorrhage, weak pulse, heart failure, nausea,

vomiting, secondary gangrene infection, ecchymosis, paralysis,

unconsciousness, nervousness, and excitability. The bite is extremely

painful, and the toxins in the venom can cause tissue damage.

How To Treat A

Rattlesnake Bite:

- The

best course of action is to keep the snakebite victim still and get

medical care as soon as possible. Cut-and-suck first aid techniques

have long been discredited as doing more harm than good. Cell

phone reception is generally good in the Sibley Volcanic

Regional Park. Simply dial 9-1-1 and inform the emergency dispatcher.

They are trained to lead you through the essential questions and they

may also make an attempt to alert park staff. And, if life

threatening, a determined ambulance driver should be able to force

his way through the gate and negotiate the rough, narrow road

to the Labyrinth. As a secondary measure, notify the regional park

staff, yourself, so that they open gates and also provide

emergency assistance.

- If

you are alone and without a cell phone, and at or near the

Labyrinth, calmly(?) walk directly to the trailhead that is

located at the Sibley Volcanic Regional Park Interpretative Center

(and rest rooms). This route is actually a rough, narrow road and not a

trail, and is one of the more traveled routes in the park, where

you will be more likely to be found by others who can render

assistance. This direct route back will prove especially

important if you become incapacitated or lose consciousness.

- Keep the snakebite victim still, as movement helps the venom

spread through the body.

- Keep the injured body part motionless and just below heart

level.

- Keep the victim warm, calm, and at rest, and transport him or

her immediately to medical care.

- Do not allow the victim to eat or drink anything.

- If

medical care is more than half an hour away, wrap a bandage a few

inches above the bite, keeping it loose enough to enable blood flow

(you should be able to fit a finger beneath it). Do not cut off blood

flow with a tight tourniquet. Leave the bandage in place until reaching

medical care.

- If

you have a snakebite kit, wash the bite, and place the kit's suction

device over the bite. (Do not suck the poison out with your mouth.) Do

not remove the suction device until you reach a medical facility.

Venomous

snakebites are rare, and they are rarely fatal to humans. Of the 8,000

snakebite victims in the United States each year, only about 10 to 15

die... but don't forget that 8,000 people are bitten each year.

A

final word of reassurance. Visitors to the regional parks are very

seldom bitten by rattlesnakes. And in virtually every snakebite case,

the victim was attempting to pick up, harass, or in some way handle the

creature.

Regarding

rituals at the Labyrinth and the law:

We feel

it necessary to include this information because a simple (but

authentic) ritual at the Labyrinth can easily rack up a considerable

number of charges, or at least a good scolding, against the hapless

visitor. Read on.

Federal

and State Law:

All birds of prey are federally protected. It is a violation of federal

law to have eagle, hawk, owl, and falcon claws, or even a feather of

such in your possession without express permission from the federal

government. Legal possession of these items is only granted

to certain American Indians for use in ritual ceremony, and museums for

public display. If you have illegal possession of such, you are

encouraged, by law, to contact the appropriate authorities and/or

return them to the land with reverence and gratitude.

Now,

the Friends of the Labyrinth (and even most park rangers) know that

illegal talons, feathers, etc used in clandestine rituals are more than

likely the result of road kill. And one may argue that it would be a

crime of conscience to allow such a magnificent bird to simply become a

grease spot in the asphalt. But that doesn't change things. But take

heart in the fact that the numerous hawks and owls (and occasional

eagle sightings) found in the vicinity of the Labyrinth are living

testimony of the success of this uncompromising attitude.

The

fact remains that most of us don't have a legal "right" to possess

these items. Do as you must, but be discreet. Read on.

The Sibley

Volcanic Regional Preserve: The

Park District's Ordinance 38, as it pertains to possible Labyrinth

activities, is summarized below. Violators will be subject to citation

or arrest. Park visitors are responsible for knowing and following

rules. For further information, ask a Park Ranger, Volunteer Trail

Patrol member, or contact the Sibley Volcanic Regional Preserve park

office.

-

Ceremonial pyrotechnics and fireworks are not permitted at

the Labyrinth, or in any regional park.

-

Fires

(and flames) are not permitted at the Labyrinth. It is also illegal to

place hot coals on the ground. Being a fire critical area, smoking

(incense, ceremonial peace pipes, calumets, etc) is also illegal. Do as

you must, but be careful and discreet.

-

It

is illegal to disturb, collect, or impede in the movements of natural

creatures within District parklands. For example, gently picking up a

snake found in a chance encounter and incorporating it in a primitive

or spiritual ritual, then returning it, unharmed, back to the place it

was found is a violation park rules. It may also soften the edge of

that creature's sharp instinct for survival.

-

A park curfew is in effect between the hours of 10:00pm and 5:00am, unless a permit is obtained to remain on

parklands. The trailhead parking lot is subject to closure 6:00pm, November through March. Again,

do as you must, but be discreet.

-

Assemblies, performances, special events or similar

gatherings require a permit. Use your discretion here.

- Gathering

of flowers, ferns, berries, and other plants found at the Sibley

Volcanic Regional Preserve is prohibited. If you intend to place

flowers in the central cairn of the Labyrinth, you are encouraged to

bring your own domestic grown flora.

-

Overnight camping is not permitted within District parklands

without a permit.

-

Beer and wine are permitted at the Labyrinth. But use

discretion.

-

Bows and arrows are not permitted on regional parklands

except at established ranges.

-

Spears, swords, crossbows and other dangerous weapons

are prohibited anywhere on regional parklands.

-

A permit is required for amplification of voice, music, or

other sounds.

|

|

|

|